Island Voices: An Island shaped by immigration

Jersey is, by nature, an Island of migrants. Lucy Layton, Jersey Heritage's Outreach Curator, discusses how migration to the Island has shaped the fabric of Jersey and our sense of Island identity.

The migration of people over many thousands of years has shaped and influenced the Island we know today. Jersey’s first permanent settlers arrived around 7,000 years ago. They were driven by a changing climate to seek a sheltered place where they could plant their crops and raise their families. They built huge stone monuments in the landscape that still stand today, permanent reminders of Jersey’s first people.

Place name evidence also reflects the movement of people. Many of the Island’s coastal areas have names of Norse origin because Viking raiders named the Island’s distinctive features as they moved through the area. Grosnez is derived from the Norse word ‘ness’ meaning a headland, L’Etacq and L’Etacquerel come from ‘stakkr’ meaning stack or large rock, Les Mielles from ‘melr’ meaning a sand dune, and Le Hocq from ‘hoc’ meaning a hook. From 931 AD, the Island was settled by Normans and inland place names are generally French in origin.

Over the past 400 years, there have been many reasons for the movement of people to Jersey, including religious persecution, political persecution and economic migration. With its geographical proximity to France, the Island has long provided a place of safety for the persecuted of that country. During the French Wars of Religion (1562 – 1598), the minority Protestant population found itself persecuted by the Catholic majority, culminating in the horrors of the Massacre of St Bartholomew when thousands of French Protestants (known as Huguenots) were slaughtered. Huguenot refugees fled the country to places of safety including London, the Netherlands and also Jersey. Although the conflict was resolved in 1598 with the passing of the Edict of Nantes that protected Protestant rights in France, this was revoked in 1685 prompting a second wave of Huguenot refugees.

Some of the Huguenot refugees who fled to Jersey during this period only stayed for a short time before moving on to Britain or the Netherlands, where they were able to freely practice their religion. However, other refugees decided to settle here permanently, and among them was Pierre Amiraux , a skilled silversmith. His influence on the craft of silversmithing in the Island is evident in the Jersey Heritage collection of Channel Islands silver. The new exhibition includes a beautiful 17th century coffee pot made by his son, Pierre Amiraux II.

In the 19th century, it was Jesuit priests who found themselves at risk of persecution from the French state. A learned society of Catholic priests with a strong interest in science, their schools were outlawed by French anti-clerical laws and Jersey provided a safe haven for their students. In 1880, they established a school in St Saviour’s Road, now the Hotel de France, and built an observatory called Maison St Louis on Wellington Hill, which still serves as a weather station today. The meteorological observations of Father Marc Dechevrens began in 1894 and have left a lasting legacy of weather reports that are still of enormous relevance today with the growing concern over climate change. In fact, artist Ian Rolls’ climate stripe mural at the Waterfront is based on Father Dechevrens’ weather observations from 120 years ago.

Jersey has also provided a safe haven for political refugees, most famously for Victor Hugo. Photographs from the 1850s depict the great French writer as a Romantic hero, exiled from his homeland by the tyranny of Napoleon III. He is depicted staring wistfully across the water to France from the Le Rocher des Proscrits (the Exiles Rock) at Havre des Pas where he lived during his three years of exile in Jersey. He was the figurehead for a group of political exiles from across Europe, including France, Italy and Poland, who had fled their home countries in the mid-19th century during a period of enormous political turbulence. Some of the exiles later returned home, but others settled here permanently. Among them was Zenon Swietoslawski from Poland, who is buried in Green Street cemetery alongside his wife and his Jersey-born son, Helier. Swietoslawski set up a printing press and published L’Homme, the newspaper of the Island’s political exiles. Such were their numbers that a corner of the cemetery at Macpela in St John was designated the exiles’ burial ground.

Over the centuries, the Island has also attracted economic migrants seeking a better way of life for themselves and their families. In the 19th century, after the Battle of Waterloo, this included retired English army officers drawn by the low cost of living. The new English residents built spacious houses and elegant terraces on the outskirts of St Helier and the town grew rapidly to accommodate a doubling of the population. Under their influence, English became much more widely spoken. They built churches with services conducted in English, British pounds replaced French livres as the official currency, and Victoria College was opened to educate their sons in the style of the great English public schools. At the same time, British labourers came seeking work on major building projects, such as the new harbour at St Helier and the breakwater at St Catherine.

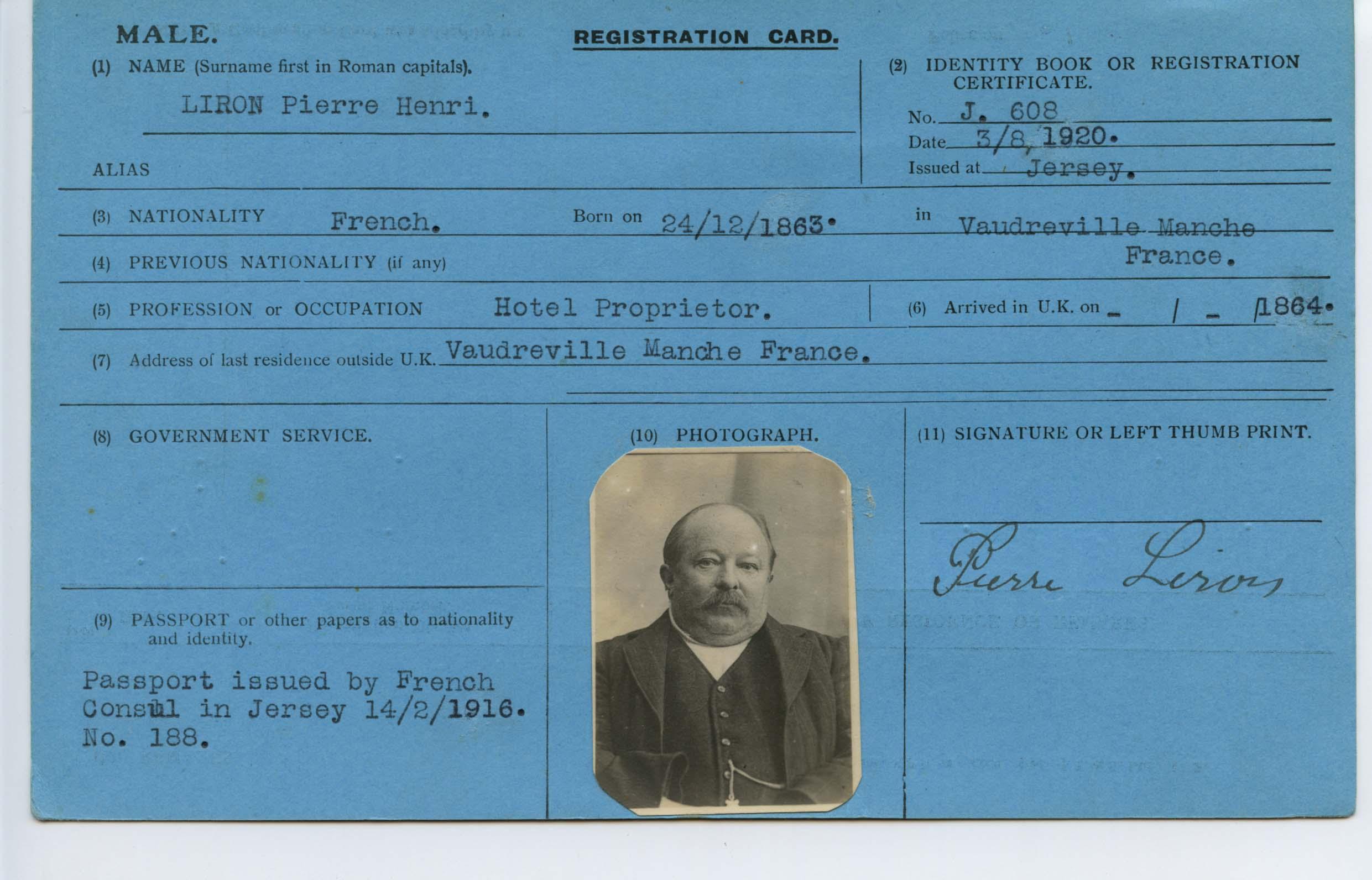

From the 1880s, French farm workers began arriving to help with the potato harvest. Some came just for the season, but others settled in Jersey and 10% of today’s Islanders can trace their roots back to our neighbours in Normandy and Brittany. Among them was Pierre Liron, the proprietor of the Soleil Levant in French Lane. He was originally from the small hamlet of Vaudreville in Normandy and his Aliens Registration Card is held at the Jersey Archive along with the records of thousands of other non-British immigrants who had to register as they entered the Island. Today, the collection is a valuable family history resource for the many Islanders who have Norman or Breton ancestry.

In the 1880s, an impressive new church was built to serve the growing French Catholic community in St Helier and it is still a distinctive part of the townscape today. St Thomas’ Church was known as ‘La Cathèdrale’ by its original French congregation and, 140 years later, it continues to play an important role in the lives of new residents from Portugal, Poland and other Catholic countries.

Discover more about the influence of immigration on the Island’s story at Jersey Museum & Art Gallery. Go to www.jerseyheritage.org for more details.