Physical location and size

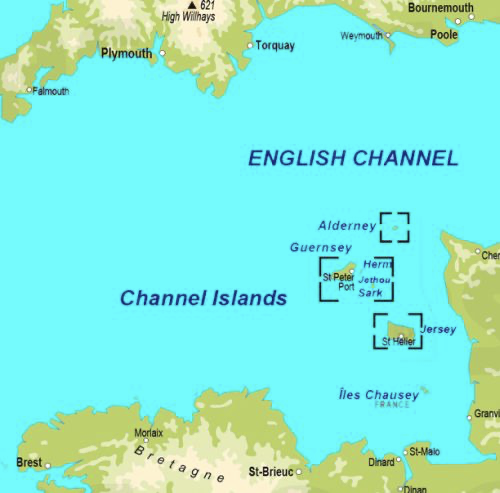

Jersey is the largest of the Channel Islands which, as the name suggests, are in the English Channel, but much nearer to the French side of the Channel than the English side. Jersey is just 22 kilometres from the Normandy coast, 56 kilometres from Saint Malo and 160 kilometres from the South Coast of England.

Jersey is very roughly rectangular in shape with a land area of 120 square kilometres. Jersey's location means that it is subject to a substantial tidal variation with the high tide being as much as 12 metres higher than the low tide. The nature of the foreshore is such that the tide in parts of the south of the Island goes out several kilometres such that at extreme low tides the size of the Island is increased by around 25%.

Jersey has long stretches of sand on the west coast (St Ouen’s Bay), the south coast (St Aubin’s bay) and the east coast (Grouville Bay) while the north coast is more characterised by cliffs and smaller bays, some of which offer small natural harbours. On the west coast sand dunes stretch some way inland.

Distinctive features

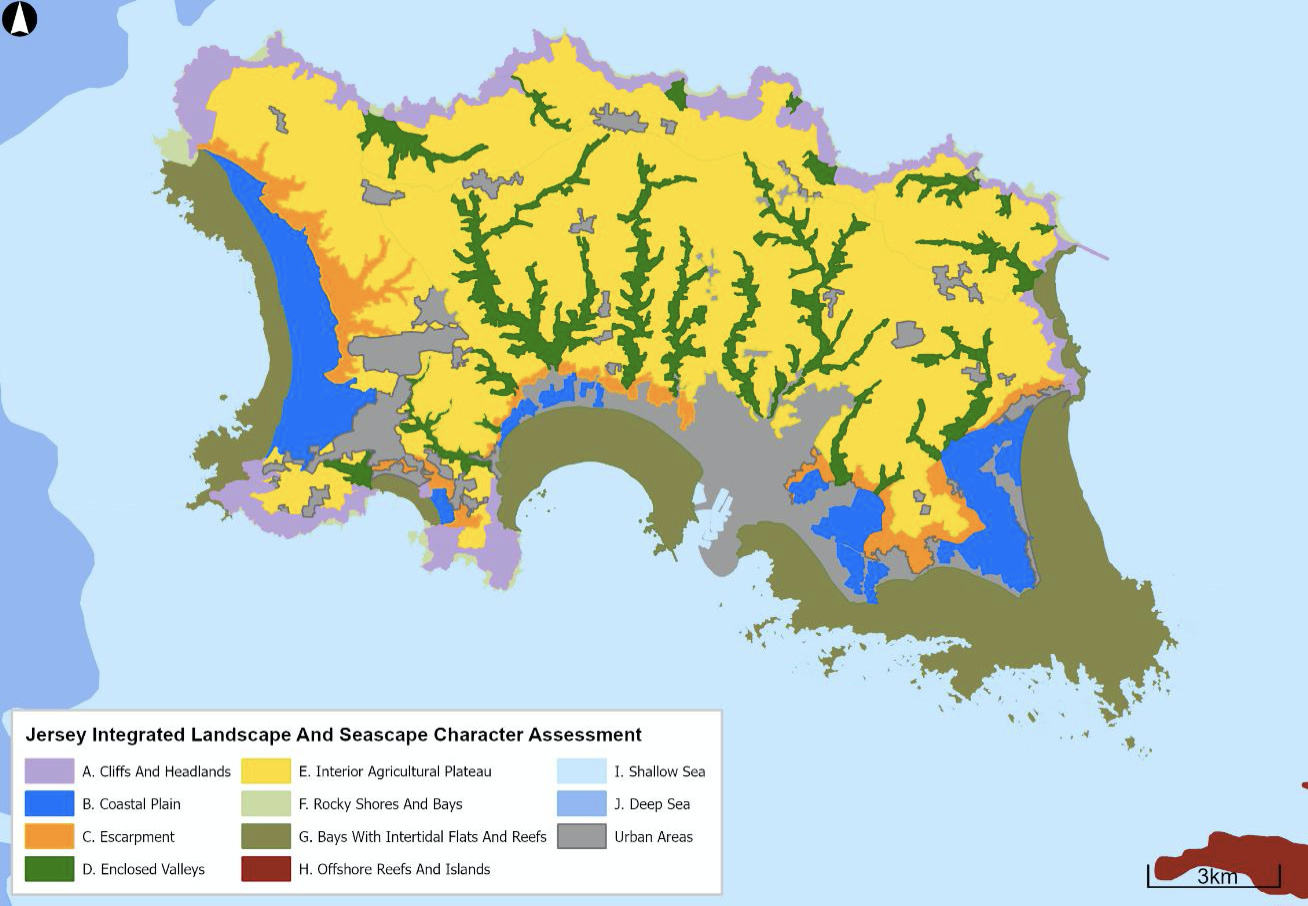

In 2020 the Government of Jersey commissioned a study, Jersey integrated landscape and seascape character assessment, as part of the preparation of a new Island Plan. The assessment, which is the source for most of this paper, listed ten special qualities of Jersey’s landscape and seascape.

Variety, uniqueness, and drama

Within Jersey’s 45 square miles, there is an extraordinary diversity of landscapes, from patchwork fields to deep wooded valleys, from rugged coastal cliffs to sweeping flat sandy bays, and from uninhabitable reefs to tranquil villages. Its unique position in the English Channel, close to the French coast, means that it is influenced by both marine and continental weather and water systems, and by a fusion of English and French culture.

Diverse and unusual geology

Jersey’s skeleton is formed of many different types and ages of igneous and sedimentary rocks, reflecting its tumultuous formation over millions of years. This combination of rocks (on land, in the intertidal zone and under the sea) leads to great diversity of landform, as well as marine features and habitats. The coasts offer opportunities to see very rare rock formations, whilst the largely- inaccessible offshore reefs are unique in Europe.

Abundance of habitats

Jersey’s waters are teeming with life, supported by an array of underwater and intertidal habitats including seagrass beds, kelp forests, maerl beds, underwater rock and reefs. Onshore, extensive dune systems provide habitats for species unique to Jersey, and wildlife thrives in the coastal heaths, woodlands, meadows and marshes. A network of hedgerows and banks provides opportunities for wildlife corridors across the island.

Spectacular coastline

Much of Jersey’s dramatic and distinctive coastline is entirely natural, from the high, rugged, granite cliffs and headlands of the north coast, to the vast sandy sweep of St Aubin’s Bay in the south. Low tide reveals a dramatic and vast world of reefs around the coast, and out to sea. The coastline also has a human legacy of fishing, vraicing (collecting seaweed to use as fertilizer), tourism and defence. Lighthouses, beacons and defensive towers form landmarks and seamarks, and add to the sense of place.

Hidden rural interior

Away from the coast, Jersey feels strongly rural, with a secretive, intimate character. Deep, dark wooded valleys cut through a plateau of patchwork fields. The rural landscape reflects generations of farming practices - from sheep, to apples, to potatoes and cattle – practices which have evolved to take advantage of Jersey’s weather, climate and soils. An intricate web of lanes, often tunnel-like between banks and trees, cover the island, linking the scattered farms and villages.

Unique prehistoric archaeology

Caves in the cliffs contain archaeological remains from the Palaeolithic period onwards, including evidence for early human life. Back then, the caves would not have been looking out over the sea, but instead over a vast plain, crossed by river channels, and it would have been possible to walk to what is now France. Later prehistoric archaeology includes La Hougue Bie, one of the most complete Neolithic burial chambers in Europe, and around the coast are visible monuments (dolmens and standing stones) and archaeological landscapes buried under sand deposits.

A rich built heritage

Traditional buildings of local warm-coloured granite occur throughout Jersey, with a distinct local vernacular style influenced by both English and French cultures. Villages vary in form, with some nestled at the foot of the coastal escarpment, and others in sheltered valley-head locations. Most villages are centred around a medieval parish church with a stone spire, which form landmarks in views across the island. Other typical Jersey buildings include manors, dovecotes, mills and structures relating to historic water uses, such as abreuvoirs and lavoirs. Farms are distinctive, often forming a cluster of buildings at the heads of valleys and accessed through a round-headed ‘Jersey arch’. Traditional farm buildings are often two storeys, with windows allowing multiple uses. Typically, the farmhouses are built to face south, and their barns are built to face east and west.

A legacy of defensive sites

Jersey’s vulnerable location has resulted in a legacy of defensive sites spanning roughly 2000 years, from Iron Age coastal forts to structures relating to German occupation in World War II. Most of the defensive sites are coastal, and include distinctive landmarks such as Mont Orgueil castle, Elizabeth Castle, the distinctive round coastal ‘Conway Towers’ and the WW II range-finding towers at Les Landes, Corbière and Noirmont, which formed part of the German ‘Atlantic Wall’.

Spectacular views

The longest and most spectacular views in Jersey are generally at the coast, where panoramas encompass land, sea and sky. This is where the different landscapes and seascapes meet, creating attractive compositions, and natural and built landmarks create focal points. Along the north coast, the offshore reefs draw the eye out to sea. The other Channel Islands and the French coast appear on the horizon. The sunsets are spectacular, particularly over the intertidal reefs. At night, dark skies over much of the island allow the stars to be appreciated, punctuated by the flashes from the lighthouses and beacons.

The varied nature of Jersey’s physical environment is illustrated in this map, which shows 11 different types of area.

Climate

Jersey has an equable climate, warm in the summer with plenty of sunshine and relatively mild in the winter. Rainfall is comparatively modest and more concentrated in the winter months. Jersey's climate can best be described as being a little more favourable than resorts on the south coast of England.

The Government of Jersey publishes comprehensive historic Climate Statistics. Table 1 shows key data:

Table 1 Jersey, key climate statistics

| Month | Mean temperature (°c) | Sunshine hours | Sea water temperature (°c) | Rainfall Millimetres | Rain days |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| January | 6.3 | 2.0 | 10 | 95 | 15 |

| February | 6.1 | 3.5 | 9 | 70 | 12 |

| March | 7.8 | 4.5 | 9 | 65 | 12 |

| April | 9.5 | 6.5 | 10 | 55 | 10 |

| May | 12.6 | 7.5 | 12 | 55 | 9 |

| June | 15.1 | 8.0 | 14 | 40 | 8 |

| July | 17.2 | 8.0 | 17 | 45 | 7 |

| August | 15.5 | 7.5 | 18 | 50 | 7 |

| September | 15.8 | 6.0 | 17 | 65 | 9 |

| October | 13.0 | 4.0 | 15 | 105 | 14 |

| November | 9.6 | 2.5 | 12 | 105 | 15 |

| December | 7.1 | 2.0 | 12 | 110 | 16 |

| Total/average | 14.5 | 5.2 | 13 | 865 | 133 |

Links with Heritage

Jersey’s natural environment cannot be separated from its history. For most of the second millennium England was either at war or in a state of tension with France. Various fortifications were built to protect the Island from French attack, taking advantage of the natural environment. Most prominent of these was Mont Orgeuil Castle, which occupies a commanding position on a hill in the east of the island.

Elizabeth Castle, St Aubin’s Fort, Seymour Tower and Icho Tower are located on the foreshore and on the coast itself is a series of Martello and Conway towers. During the Second World War the German occupying forces built a number of fortifications in prominent geographical locations.

Importance of the natural environment to Jersey's economy

Jersey’s economic history has been largely shaped by its natural environment. As early as the 13th Century ships carrying wine from France and the Mediterranean to England hugged the coast so passing close to Jersey and indeed the proceeds of shipwrecks proved to be a valuable addition to the economy. After Jersey became part of the English Crown in 1204 the conflict with France meant that Jersey became fortified, providing a natural boost to the economy.

Now, the sea is often seen as a barrier but before the advent of modern forms of transport the sea was more of a highway and Jersey’s location enabled it to prosper in trading goods as diverse as cider and stockings. With everyone living close to the sea fishing has been an integral part of the Jersey economy for many centuries and this developed in such a way that the huge cod fishing industry developed in the 18th and 19th centuries. The sea provided another additional valuable resource in the form of vraic, a type of seaweed, which has been available in plentiful amounts and has served both as a fertiliser and as a source of fuel.

The north to south slope of the Island with the resultant streams has provided the basis for water Mills which were essential to grind corn.

| User | Area Vergées | Percentage of total |

|---|---|---|

| Cultivation | 62,902 | 52.2 |

| Natural environment | ||

| Woodland | 6,786 | 5.6 |

| Grassland | 3,862 | 3.2 |

| Scrub/bush | 6,218 | 5.1 |

| Other | 4,718 | 3.9 |

| Total | 21,585 | 17.9 |

| Island water | 929 | 0.9 |

| Inter-tidal | 216 | 0.1 |

| Built environment | ||

| Building | 6,060 | 5.0 |

| Gardens | 12,137 | 10.0 |

| Roads | 3,821 | 3.1 |

| Driveways | 3,363 | 2.8 |

| Car parks | 1,127 | 0.9 |

| Pavements | 1,020 | 0.8 |

| Other | 2,038 | 1.7 |

| Total | 29,566 | 24.5 |

| Total | 120,511 | 100.0 |

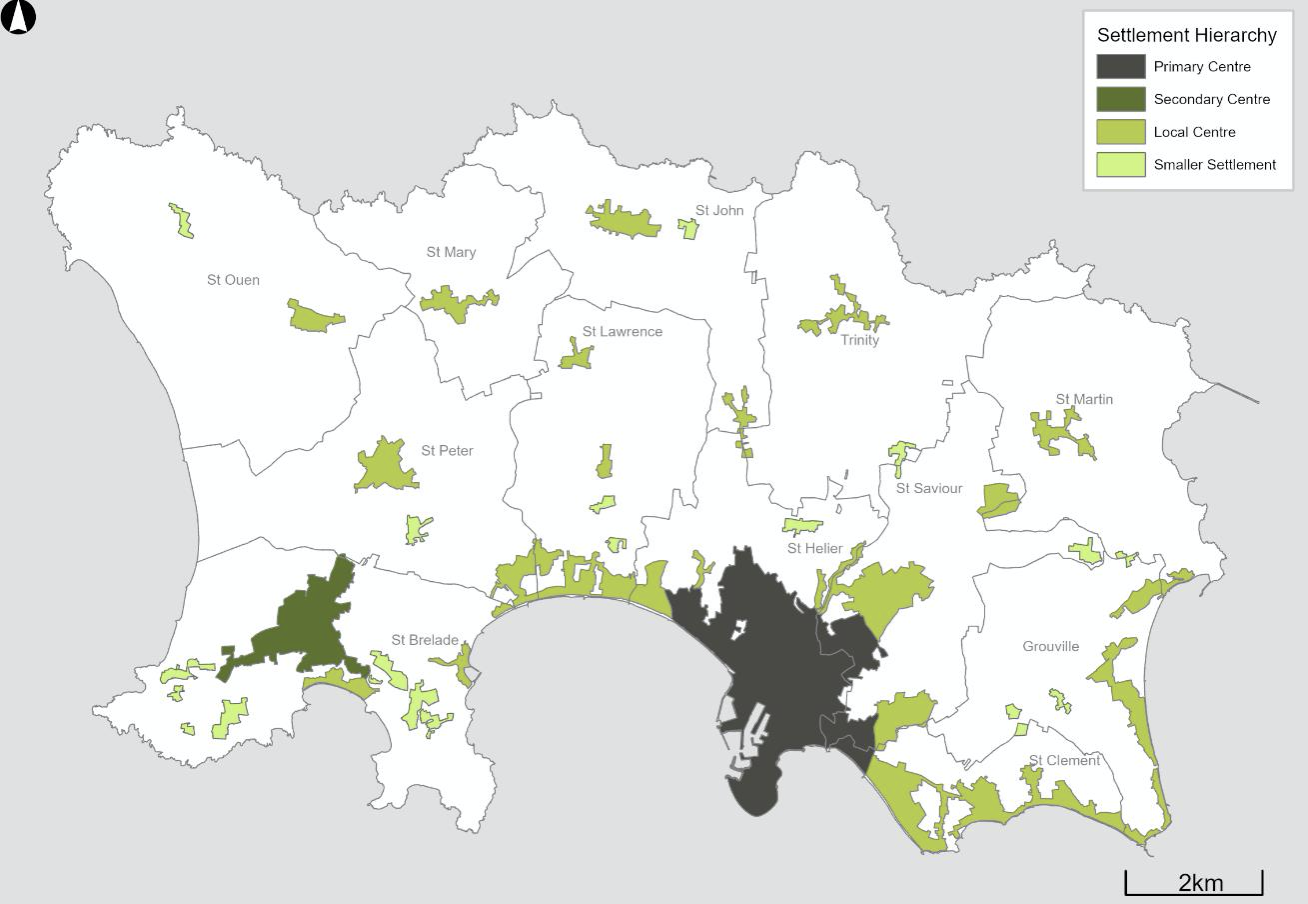

Table 2 shows that 5% of Jersey’s land is accounted for by buildings and of this about half is housing. It will be noted that gardens and driveways account for much more land than housing. The paper on parishes showed that population is concentrated in the southern parishes. This is illustrated in the map below which shows settlement patterns.

The map clearly shows the primary population centres in St Helier and the secondary centre in St Brelade. The local centres are predominantly based on the centres of the country parishes.