Jersey’s international links

Jersey is a small island, but has been outward looking with strong trading, family and other links not only with its near neighbours, France and the UK, but also further afield. These links have been driven by a combination of Jersey’s geography, history and political status together with external factors. Its outward looking nature has influenced internal developments.

Geography and history

Jersey is a small island just 15 kilometres from the Normandy coast and 42 kilometres from Saint Malo, but 160 kilometres from the South Coast of England. Its island nature has meant that fishing has been an important economy activity. As boats became bigger so the activity expanded from mackerel and conger eels in local waters with exports to France in the 13th Century, to the development of a large cod-fishing industry centred on what is now Canada in the 19th Century.

Jersey is also strategically placed on the shipping route between western France and further afield to England. In the early days, boats hugged the coast for navigational and safety reasons. Jersey, but more particularly Guernsey, served as ports of call and safe havens. Strong tides, variable weather and reefs make the seas around Jersey dangerous, and many ships foundered, the Island reaping a modest benefit from the resulting wrecks.

Jersey’s links with Normandy are much more than geographical. In about AD933 the Duke of Normandy, annexed the Channel Islands and Jersey became firmly in the Norman world. In 1066 the then Duke of Normandy defeated King Harold of England in the Battle at Hastings and became King William I of England. The ultimate source of authority in Jersey and the other Channel Islands had also become the holder of the Crown of England.

In 1204 Normandy and England separated but with Gascony and the Channel Islands being retained by the English Crown. The move of Jersey’s allegiance from the Dukes of Normandy to the Kings of England became formalised with the Treaty of Paris in 1259, under which the English Crown gave up its claim to France, other than Gascony. In 1294 England lost Gascony to France leaving the Channel Islands and Calais as the only remaining “French” possessions of the English Crown. Calais was lost in 1558.

However, for much of the next 600 years after the loss of Gascony England and France were either in a state of war or a state of tension. As a result, Jersey was heavily fortified by English Kings, the results of which form much of the Island’s rich heritage today. But throughout that period Jersey’s proximity to France meant that trading continued with France, some legal and some not legal and between 1483 and 1689 Jersey was granted neutral status in these conflicts by Papal Bull issued by Pope Sixtus IV.

Patterns of immigration into Jersey

From the 16th Century to the 19th Century Jersey became the home for French religious refugees. French protestant refugees first came to Jersey in the mid-16th Century and there was a particularly large influx between 1585 and 1588. There is no indication of the numbers involved although it was such that it was necessary to have an extra market day each week. Following the revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685, the flow of refugees increased significantly. Generally, the refugees were entrepreneurial and industrious, and contributed significantly to the economic development of Jersey.

From 1789 there was a further burst of immigration, this time predominantly of Roman Catholic priests following the French revolution. There may have been as many as 4,000 refugees, doubling the size of St Helier’s population.

In 1848, as a result of the political upheavals in that year, there was a rather different inflow of refugees, not only from France (among them Victor Hugo) but also from Russia, Poland, Hungary and Italy. A final burst of French refugees occurred in the early 1870s as a result of anti-clerical laws passed by the Third Republic.

Beginning in the early 19th Century there was a very different wave of immigration - economic migrants seeking to benefit from, and contributing to, the booming Jersey economy. The population nearly doubled between 1821 and 1851, and probably increased in the 30 or so years before by around 40%. This population increase was almost entirely caused by immigration. The major construction projects, particularly Fort Regent and St Catherine’s breakwater, required amounts of labour that could not be met from within the Island. Building workers were attracted from Scotland and Ireland in particular. The 1851 Census recorded that 27% of the population had been born in the British Isles other than Jersey. There was a notable doubling of the Irish born population, from 1,357 in 1841 to 2,704 in 1851 and there was an Irish quarter in St Helier central on Clare St. and Sligo Lane.

From about 1820 the Jersey economy also experienced the first inflow of wealthy immigrants, largely retired military officers and senior officials from the colonies, attracted by the tax regime and way of life. It was estimated that there were 5,000 English residents in the early 1840s. To a large extent they were middle class, did not work and seemed to have kept their distance from the local community. However, their local spending power would have created local jobs.

From the 1840s to the middle of the 20th Century there was a steady flow of migrant workers from Brittany and Normandy to Jersey, particularly to work in agriculture. Most probably intended to be short term migrants, planning to return to France. But some decided to settle in Jersey, many of today Jersey’s population being descended from them. There was a fairly steady increase in the French-born population of almost 4,000 between 1851 and 1901, at a time when the total population fell by 4,500. As a consequence the proportion of the population born in France rose from 3.5% to 11.4%. In addition, as the 1891 and 1901 censuses show, many of the French immigrants settled in Jersey and had children who, although Jersey-born, were part of the French community. In 1901 31% of children born in Jersey had fathers who were French.

The population remained fairly stable in the inter-War period. Post-War there has been continued economic expansion which has brought with it new waves of immigration. The tourism industry rapidly became the dominant industry. But tourism required a large volume of relatively low cost labour. Jersey turned first to Italy, then Spain and then Portugal, more specifically Madeira, for staff to work in hotels, cafés and restaurants. The 1961 census recorded 118 Portuguese (0.2% of the population). In 1981 the number of Portuguese was 2,321 (3.1% of the population) and it increased further to 3,439 (4.1%) in 1991, 5,137 (5.9%) in 2001 and 7,031 (7.2%) in 2011, the largest pro rata Portuguese minority anywhere in the world.

Jersey was also attractive to young Britons. Those who worked in Jersey for a season could also avoid tax in both the UK and Jersey as they were entitled to a full personal allowance in each jurisdiction.

More recently, since a number of East European States joined the European Union in 2003, Jersey businesses have sought to meet their labour needs from Poland and increasingly Romania. The 2021 census recorded 2,808 people who had been born in Poland. As a result of the UK’s departure from the European Union, nationals of the remaining EU countries living in the British Isles have had to apply for settled status if they wish to continue their residence. The numbers of those applying gives some additional information on the current make-up of the Jersey population. As at 30 June 2021 17,550 EU nationals had applied. Of this total 9,980 (57%) were Portuguese, 3,219 (18%) were Polish, 1,765 (10%) were Romanian and 606 (3%) were French.

Jerseymen becoming established in America

Waves of immigration into Jersey have been matched by waves of emigration, some on the back of the fishing and related shipping industries and some of entrepreneurial people seeking a life somewhere larger than Jersey.

From about 1660 there was some migration from Jersey to the eastern seaboard of America, which was driven by a combination of reasons including religion, trade and a wish to escape from poverty. The settlement was concentrated in the Boston area, in particular Marblehead, Newburyport and Salem. Among the most prominent of the settlers from Jersey was Philippe Langlois, born in Jersey in 1651, who settled in Salem and built up a significant trading business. He abandoned his Jersey name, to become John English.

A prominent Jerseyman to make his mark in America was John Cabot. He was born in St Helier in April 1680 and left Jersey for America around 1700. He rapidly built up a successful trading and shipping business, operating a fleet of privateers carrying opium, rum, and slaves. John Cabot’s children married into other leading Boston families and his descendants held prominent positions in Boston society, being eminent in trading, privateering, medicine, industry and the army and navy. Direct descendants include George Cabot (US Senator and Secretary of the Navy), Oliver Wendell Holmes (Supreme Court Justice), Henry Cabot Lodge (US Senator), Henry Cabot Lodge, grandson of his namesake (vice presidential candidate and Ambassador to South Vietnam and Germany) and John Kerry (US Secretary of State and currently President Biden’s Special Envoy on Climate).

The Jersey settlement of Canada

By the 16th Century Jerseymen has expanded beyond fishing for mackerel and conger eels in local waters to large scale cod fishing in North American waters. The nature of the industry is comprehensively explained in Rosemary Ommer’s book. From Outport to Outpost, A Structural Analysis of the Jersey-Gaspé Cod Fishery, 1767-1886 (McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1991).

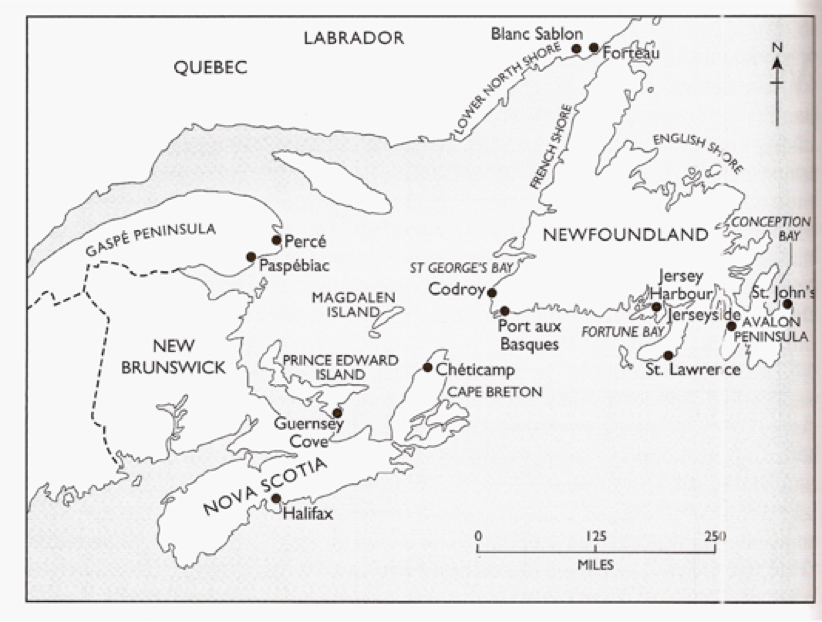

The first trading posts were established in the late 17th Century in Newfoundland, particularly Conception Bay, Trinity Bay and the aptly named Jersey Bay. There is significant similarity between place names in Newfoundland and those in Jersey, suggesting a significant Jersey influence.

The main expansion was between 1770 and 1790, initially in Harbour Grace and then Arichat in Cape Breton Island. A number of Jersey firms, in particular Charles Robin & Co, Le Boutillier Brothers and Janvrin & Janvrin, came to dominate the industry around the Gaspé passage. Janvrin Island in Nova Scotia is named after John Janvrin. The largest company, Charles Robin & Co, operated from a base in Paspébiac, although it was firmly controlled from Jersey. This and other onshore bases in Port Daniel, Grande-Rivière, Percé, Gaspé and Grande-Grave, were staffed largely by young men from Jersey. Typically, they arrived in the spring and left in the autumn, although some stayed for one winter and some for as long as five years.

It is estimated that there were about 1,200 Jersey people in Canada in 1837. The Jersey-based cod trade and maritime business generally declined rapidly after the 1860s, both contributing to and suffering from the bank failures in Jersey. It is understood that Jersey-French was widely spoken, to the extent that it was the dominant language in some areas, and that it survived into the middle of the 20th Century.

In the same way as economic migrants to Jersey have married local people and made their homes in the Island so Jersey’s own economic migrants settled on the east coast of Canada where their descendants live today. As very few Jersey women worked in the fishing industry the Jersey men married local women. People from Jersey seemed to have a disproportionate influence on local life. The Encyclopaedia of Canada’s people records –

People from Jersey and Guernsey also dominated local political life, where their influence far surpassed their meagre numbers but was an accurate representation of their social position. They were mayors, town councillors, sheriffs, custom agents, justices of the peace, school commissioners, secretaries of municipal councils and school boards, postmasters and telegraph operators. Living among largely illiterate populations, the Channel Islanders appear to have benefited from their few years of education.

Today, there is a Gaspé-Jersey-Guernsey Association, dedicated to the collection of artefacts, documents and other information relative to the history of the early settlers from the Channel Islands on the Gaspé Coast. Its genealogical records and reference books are housed in the Kempffer House Genealogical Room in New Carlisle, Quebec.

Economic migration to Australia and New Zealand in the 19th Century

During the 1850s and 1860s, the economic downturn in Jersey led to emigration to Canada (separate from the Jersey cod fishing Industry), the USA and, following the discovery of gold, to Australia. However, unlike in Canada there were no Jersey “settlements” established. Between 1883 and 1885 some 500 Jersey people emigrated to New Zealand, influenced by the depressed local economy and the offer of free passage to New Zealand as part of that territory’s policy of rapidly increasing its population. There has been a steady flow of migrants from Jersey to Australia and New Zealand subsequently and there are significant numbers of people in both countries with Jersey ancestry, many of whom feel a significant affinity with the Island.

Emigration to England

The economic downturn in the second half of the 19th Century led to significant emigration of Jersey people to England. By 1881 it is estimated that 10,000 Jersey-born people were living in England and Wales, a number equal to 27% of the Jersey-born population living in Jersey. By 1921 these figures had increased to 13,000 and 37%. A reasonable estimate for the proportion today is 50%, that is 26,000 Jersey-born people living in England compared with 52,000 living in Jersey.

In the Second World War the German occupation led to many Jersey people becoming refugees in England. The 1951 census report estimated that the Jersey population fell by 10,000 between mid-1939 and the end of 1940. Most of those evacuated immediately prior to the German occupation were taken to the North West, particularly the towns of Barnsley, Bradford, Brighouse, Bury, Doncaster, Halifax, Huddersfield, Leeds, Nantwich, Oldham, Rochdale, St Helens, Stockport and Wakefield. Some also went to Glasgow while others settled in the South West. Following the Liberation, most Jersey people returned home although some chose to remain in what had become their new homes.

Around 1524, Giovanni de Verrazano became the first European to explore New Jersey. He sailed along the coast and anchored off Sandy Hook. The colonial history of New Jersey started after Henry Hudson sailed through Newark Bay in 1609. Although Hudson was British, he worked for the Netherlands, so he claimed the land for the Dutch. It was called New Netherlands.

Small trading colonies sprang up where the present towns of Hoboken and Jersey City are located. The Dutch, Swedes, and Finns were the first European settlers in New Jersey. Bergen, founded in 1660, was New Jersey's first permanent European settlement.

In 1664 the Dutch lost New Netherlands when the British took control of the land and added it to their colonies. They divided the land in half and gave control to two proprietors: Sir George Carteret (who was in charge of the east side) and Lord John Berkley (who was in charge of the west side). The land was officially named New Jersey after the Isle of Jersey in the English Channel. Carteret had been governor of the Isle of Jersey.

Sir George Carteret (1609-80) is the key person in understanding the links between Jersey and new Jersey. His role is described in the article The New Jersey Venture, published in the 1964 Société Jersiaise Bulletin on which this section is based. Sir George was part of the de Carteret family, a long-established prominent Jersey family. He was the nephew of Sir Philippe de Carteret, Bailiff and Lieutenant Governor of Jersey from 1627 to 1643. George (who dropped the de from his name) made his name as an English naval officer. When the English Civil War broke out in 1642 it was George who ensured that Jersey remained loyal to the Crown. In 1643 George succeeded Philippe as Bailiff and in effect became dictator of the Island. He was knighted in 1644 and appointed Vice Admiral of Jersey, while at the same time operating as a privateer. In 1647 and 1648 King Charles I was trapped in the Isle of Wight. Carteret made unsuccessful attempts to rescue him and bring him to Jersey. In 1649 Charles I was executed. Jersey duly proclaimed his exiled son, Charles II, as King. Charles sought refuge in Jersey in 1649 and was financially supported by the Island. In 1650 he left Jersey for Scotland and gave Carteret a group of rocky islands, Smith’s Isles, off the coast of Virginia. Carteret named them New Jersey, but an attempt to occupy them failed.

In 1651 the Civil War ended and Oliver Cromwell was proclaimed Lord Protector. The Commonwealth attacked Jersey and Carteret surrendered in 1651 and was removed from office. The Monarchy was restored in 1660 and the King immediately rewarded Carteret by appointing him Vice Chamberlain of the Royal Household and Treasurer of the Navy and awarded him manors in Cornwall and Devon.

In March 1664 the King awarded his brother, the Duke of York, the land that is now New York and New Jersey. The Duke immediately granted Carteret and a fellow courtier, Sir John Berkeley, the areas of land between the Hudson and Delaware rivers, the boundaries of which are those of New Jersey today. Sir George never visited New Jersey. He and Berkeley appointed Captain Philip Carteret (son of Sir George), just 26 years old, as Governor. Philip arrived in New Jersey in August 1665 and named the landing point Elizabeth, after Sir George’s wife, and proclaimed it the capital.

Philip had to face conflict from some of the settlers. In 1672 James Carteret, the second son of Sir George, arrived in the province and became the focal point for discontent. Philip saw off this challenge, but in 1673 the Dutch captured New York and took over New Jersey, which they named New Orange. This was short-lived, the two provinces reverting to England the following year.

Philip governed the whole of New Jersey until 1674 when Berkeley sold his interest leaving Carteret governing what was known as East Jersey. Philip died in 1682 and East Jersey was sold under Sir George’s will. New Jersey was duly settled by immigrants from the British Isles, but as far as is known none were from Jersey. So in practice Jersey’s association with New Jersey lasted just 16 years. There are few place names in New Jersey named after Jersey. There is a borough called Carteret in the north east corner of the state, but it was given its name only in 1922. Jersey City is just across the Hudson River from New York and today is the second most populous city in New Jersey, with a population of about 260,000. The city dates back to 1804 when former US Treasury Secretary, Alexander Hamilton, helped to create the Associates of the Jersey Company to lay the groundwork for Jersey City by private development. Jersey City was formally incorporated in 1820.

On 28 January 2020 St Helier formally twinned with Trenton, the capital of New Jersey. This followed a visit to Jersey by the Mayor of Trenton in 2019. During that visit a new open space in the Jersey International Finance Centre was named Trenton Square.

Jersey's international status

It is accepted that the UK has responsibility for defence matters and that the Crown Dependencies do not have their own defence capabilities. The UK government does have responsibility for the international relations of the Crown Dependencies but in practice it is recognised but they have their own distinct identity. Jersey’s position was formally recognised in a 2007 document agreed by the British and Jersey Governments - Framework for developing the international identity of Jersey. The purpose of the document was “to clarify the constitutional relationship between the UK and Jersey, which works well and within which methods are evolving to help achieve the mutual interests of both the UK and Jersey”. The three key provisions of the framework are –

- Jersey has an international identity which is different from that of the UK.

- The UK will not act internationally on behalf of Jersey without prior consultation.

- The UK recognises that the interests of Jersey may differ from those of the UK, and the UK will seek to represent any differing interests when acting in an international capacity.

Jersey and the other Crown dependencies can negotiate international treaties if they have been authorised by the UK Government to do so – a process known as “entrustment”. When the UK ratifies any international treaty, this only includes the Crown Dependencies with their consent. The UK Government will consult the Crown Dependencies at an early stage on their wishes.

Only sovereign states can be full members of international organisations. Jersey is therefore included in the UK’s membership of the United Nations and the Commonwealth.

There is, however, a Jersey branch of the Commonwealth Parliamentary Association. Branches can be formed within legislatures of members of the Commonwealth and their dependencies.

Jersey is a member of the Assemblée Parlementaire de la Francophonie, an organisation for parliaments which have French as an official language.

Jersey is a member of the British-Irish Council comprising the UK, the devolved administrations in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, the Crown Dependencies and the Republic of Ireland. This was established under the 1998 “Good Friday Agreement”, which was the culmination of the peace process in Northern Ireland. Its aim is to “promote the harmonious and mutually beneficial development of the totality of relationships among the peoples of these islands”.

Jersey is a member of the British-Irish Parliamentary Association, established in 1990, the membership of which mirrors that of the British-Irish Council.

International relations

In the immediate post-War period, there was little need for Jersey to have an external relations policy. This changed largely for two related reasons –

- The most significant political development for Jersey in the post-War period was Britain’s accession to the European Economic Community in 1972. Jersey had grown prosperous through its strong connections to the United Kingdom while being able to be sufficiently different through using its tax system to attract people and business to the Island. Britain's entry into the European Economic Community threatened this position. If Jersey was inside the European Economic Community, then much of its autonomy would be lost but if it was outside the Community then the close economic links with Britain on which it depended would be severely damaged. In the event, a special arrangement was negotiated which gave Jersey and the other British Crown dependencies the best of both worlds, that is being within the common external tariff of the European Community but otherwise outside of the single market provisions. Subsequently, Jersey has needed to keep abreast of EU developments, particularly those relevant to its financial services industry. Together with Guernsey it established an office in Brussels to strengthen its capability in this respect. Britain’s exit from the EU has similarly required a great deal of work to ensure that the Island’s interests were recognised and protected, with fishing matters presenting particularly difficult challenges.

- Jersey’s development as an international financial centre together with a growing trend for financial services to be regulated according to internationally agreed standards.

Jersey’s external relations is the responsibility of the Minister for External Relations. Policy is set out in its Global Markets Strategy. The strategy is summarised as follows -

The objectives of the Global Markets Strategy are to increase Jersey’s visibility, improve access to decision-makers and facilitate business flows with priority global markets– leading to positive contributions to the Island’s jobs and growth objectives. The strategy also seeks to maintain and strengthen Jersey’s reputation as a high-value, well-regulated, international finance centre of choice for target markets in Africa, Asia, the Middle East and North America.

The strategy places emphasis on the importance of building broad-based and sustainable government-to-government relationships across a range of common interests. The strategy therefore proposes a tailored approach to Jersey’s engagement with priority global markets based on careful identification of shared interests and opportunities for cooperation.

Jersey's relationship with the EU

Prior to the UK’s departure from the European Union (EU), Jersey’s relationship with the EU was set out in Protocol 3 of the UK's 1972 Accession Treaty.

In practice, this means the Island was treated as part of the European Union for the purposes of free trade in goods, but otherwise was not a part of the EU. Following the UK referendum on EU membership, one of the island's key objectives was to protect, as far as possible, the Island’s key interests – including its relationship with our European partners.

Jersey’s relationship is now enshrined in its membership of the UK-EU Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA), which was reached prior to the end of the Transition Period on 31 December 2020. This means that Jersey goods bound for the EU are treated as they would if they come from the UK. In addition to the practical implications of the UK’s exit, Jersey has maintained long-standing relationships – politically, economically and culturally – with its closest French neighbours and partners across the EU. The Channel Islands Brussels Office (CIBO) makes sure that Jersey’s interests are promoted in Europe, and acts as the central engagement point with Brussels and within other multilateral fora.

Channel Islands Brussels Office website

The Bureau des Îles Anglo-Normandes promotes the interests of the Channel Islands in France. Located in Caen, its mission is to promote and help political, economic, cultural, educational and operational links with the French government and its institutions at departmental, regional and national levels.

Bureau des iles Anglo-Normandes website

Overseas Aid

Jersey runs its own overseas aid programme. The programme is overseen by the Minister for International Development, who heads a six-person commission. Jersey Overseas Aid’s annual budget is currently 0.30% of Jersey’s GVA, £22 million in 2025. It has four primary funding themes –

- international development grants

- emergency and disaster relief

- Jersey overseas charities

- community works programmes and bursaries

The development grants account for most of the budget. They fund multi-year projects run by major charities and concentrate of carefully chosen themes.:

- Financial inclusion - designed to increase access to basic financial services such as loans, savings, money-transfers and insurance to struggling families currently excluded from formal banking in Zambia, Rwanda and Sierra Leone.

- Conservation livelihoods, based on the premise that protecting the environment can be a virtuous circle if programmes, are designed to tie human well-being and conservation together. Programmes are currently running in Malawi, Zambia and Ethiopia.

- Dairy for development. The largest single development grant awarded in 2019 was for a dairy project, based in Rwanda. The Annual report states: “Dairy initiatives represent the agency’s flagship projects; not only do these life- changing interventions utilise Jersey’s internationally renowned Jersey cow, they also use the island’s considerable expertise to advance the wellbeing of thousands of households. The island is uniquely well-placed to assist farmers, charities, cooperatives, extension workers and national governments with improving the quality and profitability of milk production.”

Sport

In respect of sport Jersey operates in very different ways in different sports ranging from competing as an independent nation to being treated as part of England. It is not unique in this respect; sporting boundaries are often different from political boundaries and are set on a sport-by-sport basis. For example, England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland compete as separate nations in world and European football tournaments. In rugby union, the “six nations” includes the team of Ireland, comprising part of the UK and the Irish Republic.

Jersey competes as a nation in international men’s cricket, its team winning the international division 5 championship in 2019.

Bowls and Petanque are particularly strong in Jersey and the Island competes in European and world championships.

Since 1958, Jersey has competed as a team in the Commonwealth Games, responsibility for which rests with the Commonwealth Games Association Jersey. Jersey athletes compete for Team GB in the Olympics, an anomalous situation since the Islands of Bermuda and Asuba, which have no greater autonomy than Jersey, compete as separate Olympic nations.

Jersey was a founder member in 1997 and has since been an active participant in the International Island Games, held every two years for islands throughout the world. Jersey hosted the games in 2015. Jersey also participates in the youth games known as the Jeux des îles.

Jersey had a prominent rugby team, the Jersey Reds, which competes in the English championship. There is a general understanding that Jersey-born players are eligible to play for any of England, Scotland, Ireland and Wales.

Jersey football teams compete in the English league system and the FA Cup. Jersey has sought to become a member of the Union of European Football Associations (UEFA), hoping to follow in the footstep of Gibraltar and compete on the international stage. However, its application was rejected on the grounds that Jersey is not seen as an independent nation by the UN. This argument overlooks that neither are Gibraltar or the Faroe Islands.

Jersey Sport, established in 2016, is an independent body tasked with championing sport and active living in the Island. One of its important roles is to administer travel grants, funded by the Government, which enable sports teams to travel to England and further afield.